Ramy ‘feels’ every shot and every situation, that’s what makes him probably the greatest player in the history of the game

By RICHARD MILLMAN – Squash Mad Coaching Analyst

At the risk of attracting all kinds of critical commentary I am going to make a bold statement: Ramy Ashour doesn’t know what he is doing most of the time.

That’s right. Not a clue.

If that’s the case, how come he is arguably the best all-round squash player the world has ever seen?

As I understand it, squash is a sport that has multiple elements.

Technical skill, physical fitness, strategy, emotional control and work ethic are the key ones by my reckoning.

Technical skill, physical fitness, strategy, emotional control and work ethic are the key ones by my reckoning.

I would place Ramy in the top one percent of technicians of all time – and when I say technicians I am talking about those whose movement and racquet skills are both at the elite level.

Movement is much more important than stroke work (which should be a facilitator of your movement), but you can’t be an elite technician without being brilliant at both.

His injuries notwithstanding, I would hazard a guess that in the area of physical fitness he doesn’t occupy such a high place in the all-time standings. Excellent, yes, but not in the top one percent.

With regard to strategy, I find it difficult to gauge. He does some peculiar things from time to time, and even seems to self-destruct on occasion. Does he forget the game plan sometimes? I don’t know – you would have to ask him.

His emotional control is an interesting one. He has bouts of self talk which are amusing, idiosyncratic sideshows, but overall I feel he has an edge that few players have ever exercised at the level that we see from Ramy. Namely – fun. Ramy absolutely loves playing squash at the highest level against the best in the world.

He loves the challenge – both from the most excellent opponents and in testing himself.

His work ethic is beyond question. There may have been players in the past who worked as hard. But I doubt that any worked on all aspects of the game more than Ramy.

So why say that he doesn’t ‘know’ what he is doing most the time?

Imagine you are crossing a busy street. You are day-dreaming, you look around and you see an eighteen-wheel truck traveling at speed toward you.

Your subconscious mind kicks into action.

Faster than you can possibly imagine, your subconscious calculates the velocity of the truck, the distance between you and the truck, the distance between you and safety, and the required velocity for you to avoid being flattened.

Provided you do actually escape, you don’t ‘know’ how you managed to do so. You are unconscious of the process that your subconscious used to mitigate your demise.

This is why I say that Ramy Ashour doesn’t ‘know’ what he is doing most of the time.

Rather he ‘feels’ what to do instantaneously. The same as your lightning response to avoiding the truck.

Most of Ramy’s opponents slow the process down by trying to ‘think,’ thereby interfering with the speed of their subconscious, by invoking their slow old conscious minds.

For my money Mohamed Elshorbagy – a brilliant player in his own right, is currently getting in his own way.

For instance, in the recent final of the World Championship between Ashour and Elshorbagy, the younger Egyptian made a number of conscious attempts to affect the outcome of various situations. Some see this as clever gamesmanship. In my own opinion it is a conscious distraction that backfires as Elshorbagy directs his attention away from process toward outcome.

Thinking about winning in any way shape or form, simply distracts a player from the process of playing at an optimum level. True, these apparent pieces of strategy may also cause the opponent to momentarily leave the automatic subconscious process and become consciously active in the distraction, but this is usually with players of lesser focus.

Winning is a consequence of excellent play. Not the focus of it.

I watched the World Open final several times and my friend, world class player Ali Walker from Botswana, who also watched it, messaged me about Ramy’s specific movement technique and we had a fruitful and interesting discussion. This discussion led to further thought and ultimately to these comments:

Richard Millman:

I like the sequential timing of his (Ramy’s) movement versus his ball contact and his control of pace to ensure that he can be in position to cover all of his opponent’s angles of possibility before the opponent can release the shot. If I am thinking of the same movement as you are – I think that creates momentum for both his flow to position and a whiplash like energy wave that he uses to propel the ball. Am I on the wrong track? What is your feeling?

Ali Walker:

(Comment withheld for privacy reasons)

Richard Millman:

I agree with you. Here’s a simple thought that I have been developing recently. Our bodies are also our weapons. We use our body mass to generate force (Newton’s Law Force = Mass x Acceleration). But that weapon can only use the force generated effectively if we have the mass (body) under control. To load the weapon we need to decelerate in a controlled manner, simultaneously loading potential ready to use. The more you extend your body the less ‘loaded’ you are and the less potential you have to utilize.

If you watch Ramy he tries to use small steps as much as possible to retain potential for both movement and stroke production. These he skillfully combines in one movement, thereby achieving incredible efficiency by using his movement to generate whatever stroke power he requires. That little leg sweep is a part of the small steps that are like little cogs in a gearing system.

Like Olympic sprinters, at the beginning of a race and after they have crossed the line, his take-off and deceleration are achieved with small steps that maximize the speed/power ratio – except when he slows down, he doesn’t do so to stop – he does so to proactively prepare for the next power surge.

Additionally, he ALWAYS expects his shots to be returned and so there is no dropping of his guard or reduction in availability of potential as he seems to WANT his opponent to retrieve his shot so he can continue the process of acceleration/deceleration. I don’t believe the rally process for Ramy is linear. I believe – like the Chinese view of time – it is cyclical.

He simply repeats his behavior dependent on which stage of the cycle he is at – acceleration or deceleration in anticipation of acceleration. As such he doesn’t recognize a linear duration and doesn’t feel pressurized by how long he has been going.

In fact if the cycle comes to an end he is more disappointed that the wheel has broken – whether it is he that has broken it or his opponent. Often he seems disappointed that his opponent can’t continue the cycle. Small, rapidly adjusting steps that keep him mentally, physically, emotionally and continually connected to the ball, allow him to play well within his available physical potential most of the time, so he has reserves for the extraordinary.

Thoughts?

(End of email discussion)

I am an analyst. I attempt to consciously study the game of squash and the great masters of the game. That means I have spent years thinking about the game – as can be seen above in the discussion with Alister. But if a player tried to ‘think’ the ideas that I have expounded above during a competitive game – well, I think you know what would happen – they’d be run over by that eighteen-wheel truck!

(In point of fact this is one of the problems for spectators and promoters of the game – the content is so multi-faceted that understanding it becomes mentally supersaturating and spectators have to detach and remove themselves before they get mentally run down by the eighteen-wheel truck of data that they find rushing at them! If it takes a world-class player years to learn and assimilate the subtleties of the game, and these thoughts then get magnified by world class athletes performing them at levels beyond the comprehension of recreational players, then what chance do spectators have of understanding the kaleidoscope of information that explodes toward them?)

To learn the game requires both the conscious mind and the subconscious mind.

The conscious to learn and digest the nuances of the game and to then diffuse these ideas into the subconscious to be able to produce them at lightning speed.

Infect the subconscious with conscious input during performance and the whole house of cards comes crashing down.

There are many squash players who have a range of extraordinary assets.

But unless you both consciously learn and understand the correct nuances when you are learning and then subconsciously assimilate and incorporate them into your automatic behavior, you can easily go off track without realizing it.

And, if you have gone off track and practised incorrect behaviors for the proverbial 10,000 hours – you are going to have spend a lot of time working on corrections – if you are even able to recognize the corrections.

No-one (yet) has so completely assimilated, automated, practiced and perfected the subtleties of the game as Ramy Ashour. The amalgam of this fact and his other assets has produced a unique individual.

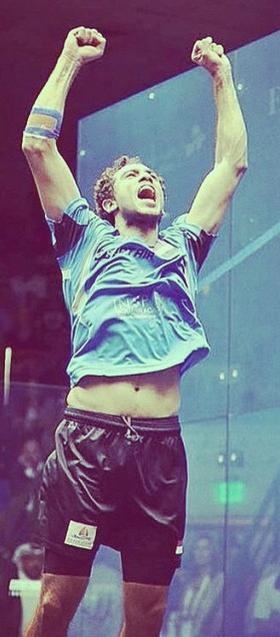

And so hail to Ramy.

An unconscious hero.

And perhaps the most complete squash player the world has ever seen.

by Richard Millman: November 28, 2014

Pictures courtesy PSA